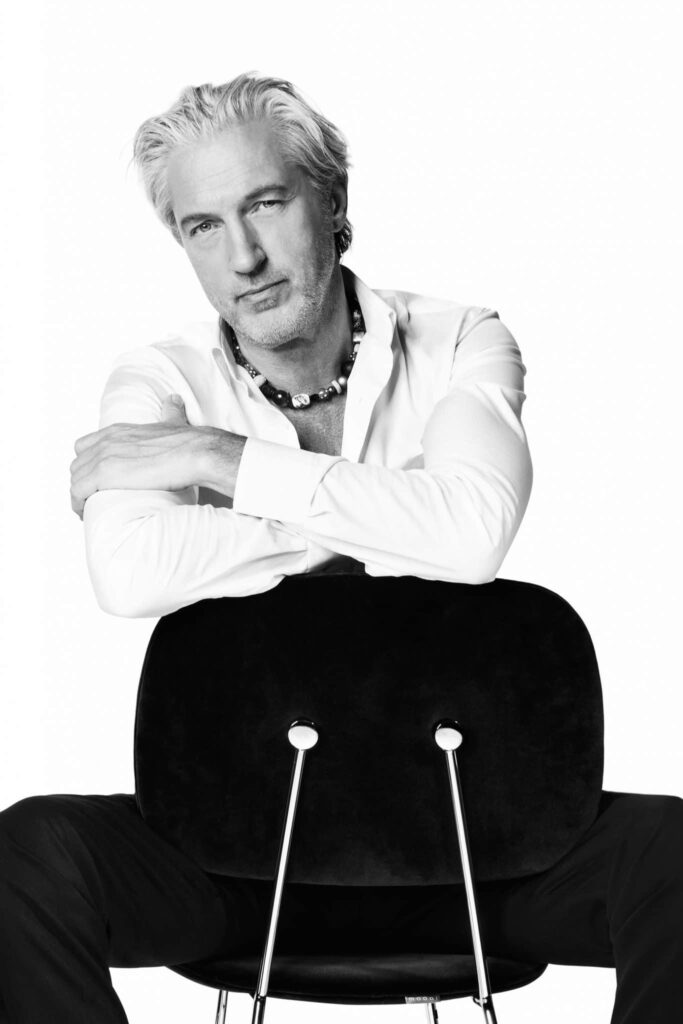

With his designs, Marcel Wanders (1963, Boxtel) builds bridges between past and future. White and black bridges, because in his work he also gives place to the darker sides of his existence. "The pain lies mainly in the fact that I don't decide: I'm never going to do this again!" he tells MASTERS.Text: Bart-Jan Brouwer | Online Editor: Mical Joseph

"I understand that the viewer takes that as a starting point, because that is the first time they see me. I myself see it differently. For me, the starting point is the moment I decided I had a vision and wanted to believe in it."

"I've had a few moments in my life when I've been confronted with that. Once when I was clearing out my mother's house, I found all the pieces of paper I had written in the past - I was really a thinker who wrote down his reflections. Even in preparation for my performance Pinned Up (2014) at the Stedelijk Museum, I dove back in time. My conclusion: nothing has changed, the fundamentals are still the same. Those are where your interests and thoughts are. Over time, you build up cones there: more information, more certainties, more evidence. Those cones merge into each other, and here and there a new point pops up. That is the model of development. It is not that there is another man standing there now. The doubts, uncertainties and hunches of the past are not gone. However, I did think about it, sought evidence. That which interested me fundamentally has not really changed. But over the years I have come to understand it more intrinsically: oh wait, so that's how it is!"Knotted Chair (1996)Cappellini New Antiques

"I am not only interested in my daughter's life, but also in my mother's life. I want them to hold each other's hand. My awareness only increases when I live by both sides. It is a waste if we cut off every day what we were yesterday. Because by doing so we also make unimportant what we are doing today. In Brabant, parents do tell their children, "If you want to learn to whistle, you have to eat the crusts of your bread. This is the subject of one of my first works, Vertelling van kinderen en bathwater from 1985 (printed in 2001 as A tale of children and bathwater; ed.). The inhabitants of a village complain about the hard crusts. This goes so far that the baker decides to make bread without crusts from now on, making bread with crusts only for himself. Years later, a little boy walking through the village is attracted by a peculiar sound. He goes

the sound and sees the baker with pursed lips producing that sound.

The little boy runs to his mother: "Mom, come! You have to hear this! The baker is making a wonderful sound with his lips.' The mother explains that this is called "whistling" and that everyone used to be able to do it when people still ate bread with crusts. Eventually everyone goes back to eating bread with crusts because they really do want to be able to whistle."

"You don't realize all that you are destroying if you don't cherish the past. Look at Thomas Edison's invention of the light bulb. At the moment of innovation, there is a fierce interest in moving away from candlelight because it's all risky. Edison wanted controllable, bright light. Then that gets into the hands of engineers and is made as perfect as possible. A logical path. In retrospect, you can say that there was very little respect for history and a lot of faith in the future. With more respect for the past, it could have been decided that instead of a constant light, for example, a lamp spread a dancing light. Not a dead light but a living, more natural light. I consciously go back to such moments in time - Lost and found by innovation I call that trajectory - searching for such inventions, looking back with love and compassion at the inabilities of the past. In hindsight I can think differently, I have that luxury. As a designer, I don't make objects that save lives - it's not like I make braking systems for Tesla - but those that keep our culture moving. You have innovation and cultural innovation. We do cultural innovation. And I think that's much more important too, because cultural innovation drives innovation. We think and want first, then execute. My kind of design changes the interaction between people and the environment. With the things I make, I give the public a different connection with the built environment. Because people don't like aging, designers mostly create metaphors about youthfulness and beauty. That babyface fixation makes everything look like it was just born. I decided not to go along with that. You just shouldn't make things that look new, shouldn't idolize the new. New in itself is not a problem, but it is when it is the main qualification: then you have a completely unsustainable product. There is no quality that is less sustainable. New is about now. For our culture, new has been the most important quality for a hundred years. It is the foundation of a disposable culture. We have to start making new really unimportant."

"I try to make work that says who I am, explains what I want to tell, reveals my love for the world and provides people with their needs. As a little boy, I liked to make presents for people. I would glue something together for my aunt and give it to her wrapped with a bow. She thought I was the sweetest little man. Early on I understood that a good gift has it in it that someone feels seen. If it is truly made for someone from love and with respect, then the person for whom it is intended feels it. Just as my work does. Actually, I make gifts for the world. My work is a celebration of the relationship between me and the world."

Want to read the entire interview with Marcel Wanders? The new MASTERS Magazine will get you through the summer. Order your copy now via the button below!

A tale of children and bathwater (1985)

© 2024 MASTERS EXPO. All rights reserved.